Payments for Watershed Services

Share

More from this series

Trout Stalker Ranch in Chama, New Mexico. Photo by Adam Schallau.

Conservation Finance Series—Part Six of Nine

By Jane Rice and Ben Guillon, WRA, Inc., with guest contributor Jeff Corbin of Restoration Systems, LLC.

Payments for watershed services totaled $24.7 billion globally in 2015, according to a recent report, The Global Status and Trends of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Payments for watershed services dominate global environmental markets, both in terms of growth and market value. There is a wide variety of payment for watershed services approaches, and programs can be developed in forest, agricultural, wetland, grassland or other ecosystem types. The underpinning concept of watershed services programs is that landowners implement practices that result in a quantifiable water quality benefit in exchange for a payment from entities that are subject to regulatory requirements or wish to lower business costs or risks related to water quality.

Given the variety of watershed payment schemes, we have provided some high-level information on watershed payment programs in the typical Q&A format, followed by a series of program examples to further illustrate how this concept applies on-the-ground. (This article does not address water rights markets, which will be the focus of part 7 of this conservation finance series.)

How do watershed services programs work?

Watershed services programs are typically developed in response to regulatory and business incentives. For example, in a regulatory context, if pollutant levels—as defined under the Clean Water Act—are exceeded in a water body, then the local water utility faces noncompliance penalties and is incentivized to reduce pollution. Instead of installing new treatment technology, the water utility could pay landowners to implement practices that reduce pollution levels in the water body. In other cases, there may not be a clear regulatory driver to address a water quality issue, but companies may choose to mitigate water quality risks because of perceived threats to their business. Examples of water-dependent industries include tourism, seafood and breweries. Watershed services schemes often address water quality issues associated with sedimentation, nutrient loading, temperature or salinity. Some programs are designed to address watershed health issues more broadly by reducing the risk of catastrophic wildfires and floods.

More often than not payments to landowners are made by national, state or local governments; however, there are many examples of private contributions as well, particularly from private developers, the food and beverage industry and foundations. The payers may contract directly with landowners or pay into a collective water fund or government program. Unlike the carbon market, there is no centralized platform for purchasing watershed services (or credits) and transactions tend to occur within watershed boundaries or other local jurisdictions. (For additional information on watershed services markets, see Ecosystem Marketplace’s report “Alliances for Green Infrastructure: State of Watershed Investment 2016.”)

What management practices may landowners be asked to implement?

Some watershed services schemes allow for landowners to choose the management practice, as long as the desired water quality outcome is achieved. Other schemes prescribe particular practices, examples of which are provided below:

- Planting trees or other vegetation to reduce erosion, reduce pollutant loadings or increase shade and reduce water temperature.

- Thinning forests to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires that lead to sedimentation.

- Building fences to keep livestock out of riparian areas and reduce nutrient and pathogen loading.

- Restoring streams and low flow dams to reduce sedimentation, nutrients and pathogens.

- Implementing agricultural practices and/or minimizing use of fertilizers to reduce nutrient loading.

How can a landowner participate in a watershed services program?

Typically a watershed services program is set up by a state or local public entity in response to a water quality issue. In some cases, a nonprofit will establish the program on behalf of a local community and manage the administrative processes and technical components. The program developers usually reach out to landowners to solicit their involvement during the design of the program.

What can a landowner expect to be paid for participating in a watershed services program?

Landowner payments are highly dependent on the local program and market. If the program is developed in response to a clear regulatory driver and economic conditions are driving the need for mitigation, payments are likely to be higher and more consistent. In the case of nutrient banking, for example, if demand for nutrient credits is high, a landowner could feasibly make over a million dollars over 10 to 20 years on a several-hundred-acre property. Although, returns depend on a variety of market factors. Additionally, landowners may benefit from improved land management and water quality on their own property, and lower risks associated with fire or erosion, as a result of the new practices associated with some watershed services programs.

What costs should a landowner expect to incur for participating in a watershed services program?

Costs incurred will depend on the program, new land management practices or land conversion required, and the landowners’ particular property and current land uses. If the program requires certain agricultural management practices, the landowner may need to absorb the cost of any new equipment and forgo prior practices and associated revenues. In some cases, the transition to new management practices could also lead to increased product revenues in addition to watershed services payments.

What risks should a landowner be aware of before agreeing to participate in a watershed services program?

Depending on the type of program, the landowner may be required to commit to participation over the long-term. In the case of nutrient banking, a perpetual conservation easement would be required. Other schemes require that the land be leased for the implementation of certain management practices. A long-term encumbrance of the property can limit a landowner’s options for future land use and therefore increases risk associated with participation. In terms of monetary risk, payments to the landowner may be made up front, after management practices have been implemented, or after water quality outcomes are demonstrated. Each of these options present different levels of risk to the landowner.

Watershed Services Payment Program Examples

Medford Water Quality Trading Program

As the City of Medford’s population grew, the wastewater treatment plant discharged increasingly warm (but clean) effluent into Oregon’s Rogue River. In order to comply with the Clean Water Act, the city was required to offset the impact of the warm water discharge. Purchasing new cooling infrastructure would cost $15 million. Instead, with the help of The Freshwater Trust (TFT), an Oregon-based nonprofit, the City opted to implement a payment for watershed services program to the tune of $6.5 million, a clear cost savings.

Under the program, TFT arranged 20-year leases with landowners to plant and maintain trees on their properties to shade the stream and cool the water. The temperature reduction is quantified using a TFT tool and tracked relative to the City’s permit requirements. To date, 27 acres (or 3.6 miles) of stream have been planted with trees. Additionally, Chinook salmon and steelhead trout are benefiting from the improved habitat in the river.

Evident keys to this program’s success include: the clear cost-effectiveness of implementing the watershed payments program instead of installing new technology; the involvement of a local nonprofit to establish and run the program; and the importance of a tool for measuring water quality outcomes relative to regulatory requirements. You can learn more about this program on The Freshwater Trust’s website: Medford Water Quality Trading Program.

Virginia Nutrient Banks

In response to excessive nutrient loadings that cause eutrophication, algal blooms and fish kills, the state of Virginia set limits, some through regulatory requirements, for the amount of nutrients entering water bodies from a variety of sources, including agriculture, septic and municipal and industrial wastewater. Virginia’s nutrient credit trading program affords these sources an opportunity to meet a portion of their required loading reductions by purchasing nutrient credits (based on Phosphorus as the keystone pollutant). For instance, a developer who builds a shopping plaza is required to mitigate nutrient loadings from construction and on an ongoing basis from the increased impervious surface.

Virginia’s nutrient credit trading program creates market-based opportunities for landowners and professional restoration companies, as well, through the development of nutrient banks. Nutrient banks reduce nutrient loadings by implementing a suite of best management practices—beyond those already required by or funded under federal or state law—on agricultural lands or by converting portions of agricultural lands to forest or hay (“Land Conversion Banks”). In addition, stream restoration projects on agricultural lands have recently been proposed for nutrient bank certification. The bank’s nutrient reduction is quantified as a credit and can be sold to regulated entities, like the developer mentioned above, in order to satisfy regulatory mitigation requirements. More often than not, it is more cost-effective for the developer to purchase nutrient reduction credits rather than providing their own mitigation onsite. There are over 100 banks in Virginia, ranging in size from less than 20 acres to greater than 200 acres.

For land conversion banks, a perpetual conservation easement or other legal instrument must be placed on the land in order to generate credits. In many cases, a professional restoration company will partner with a private landowner to develop the nutrient bank. The partner company may offer to compensate a private landowner for a portion of their land or for the value of the conservation easement, in order to develop a nutrient bank on their property. In some instances the two parties will negotiate a credit cost-share agreement. The nutrient bank must be approved of by regulatory and natural resource agencies before credits can be sold. Typically, a 200-acre bank will produce 200 credits, or 1 credit for 1 pound of phosphorous reduced on one acre. Credits sell for $13,000 to $25,000 each, depending on the regional supply and demand dynamics. Nutrient bank development costs are about $7,000 per credit on average, but can vary significantly. In deciding whether or not to develop a nutrient bank, landowners will need to consider the particular cost and revenue projections for their land, including the cost of changing management practices or taking a crop out of production in order to create the bank. In addition, the overall supply of existing credits and demand for future credits should be carefully analyzed.

Since 2009, in excess of $50 million worth of credits have been transacted through Virginia’s program. These credits represent several thousand pounds of phosphorus reductions; however, millions of pounds of reductions are needed in the state and the program could be scaled up significantly. Other states could replicate Virginia’s program with clearly defined regulatory water quality standards to drive nutrient reductions, transparency as to how credits are defined in relation to management practices, and strong demand, which usually parallels economic growth and development. North Carolina has a similar state nutrient reduction program where developers and wastewater facilities can satisfy a portion of nutrient reduction requirements by purchasing nutrient offset credits. Practices that generate nutrient credits in North Carolina include: restoring riparian areas, soil improvements, stormwater control measures and cattle exclusions.

Rio Grande Water Fund

Catastrophic wildfires lead to erosion and sedimentation that impair downstream water supplies for communities and businesses. Water funds provide a vehicle for downstream stakeholders to collectively pay for forest health treatments that increase watershed resiliency against catastrophic fire. Water utilities as well as water-dependent businesses, nonprofits and community members pay into the water fund and the financing is used to pay private landowners or public land managers to thin forests, conduct prescribed burns or implement other practices that reduce the risk of fire. Forest health treatments are funded in priority areas, based on fire risk assessments and in some cases risk reduction outcomes are measured and reported to the payers.

The Rio Grande Water Fund was launched in 2014 and has since raised $3.64 million in private funding and $30 million in public funding, and has restored 70,000 acres using thinning and controlled burns. Over the last three years, 900+ acres have been restored on private lands and fire management training was provided to private landowners and public agency staff. Treatments are also being conducted on national forest land. Payers include the Albuquerque Water Authority and a variety of foundations, cities, councils, the USDA Forest Service, state agencies, and breweries. The Rio Grande Water Fund is sponsored by The Nature Conservancy and you can find the program’s 2017 Annual Report on their website.

Am I a candidate for a watershed services payments?

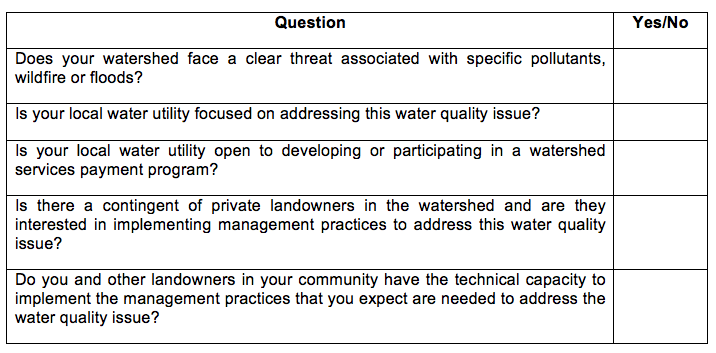

Given the variability of watershed services programs and the need for a local entity to champion the development of the program and coordinate landowners and payers, it is a bit more difficult to determine the opportunity for a specific landowner in this space, compared to other environmental markets. However, the brief checklist below can help you think through the necessary components for developing a watershed services program. If you answer “yes” to all of these questions, you may be a strong candidate for a receiving watershed payments. If you have questions or would like to request additional information, please do not hesitate to reach out to us.

WRA, Inc. offers professional consulting services in plant, wildlife, and wetland ecology, water resources engineering, regulatory compliance, mitigation banking, conservation finance, environmental planning, GIS, and landscape architecture. WRA is a national leader in the wetland and species banking industry and recently developed the largest bank in the country. WRA’s conservation finance team is pioneering new monetization approaches across carbon, water, species, and ecotourism markets.

Restoration Systems, LLC is a leading turn-key environmental restoration and mitigation banking firm with more than 50 mitigation banks and restoration sites in nine states. Their ecologically beneficial activities are funded by the sale of compensatory ‘mitigation credits’ required by state and federal agencies that regulate development in sensitive areas.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Publishing this content does not constitute an endorsement by the Western Landowners Alliance or any employee thereof either of the specific content itself or of other opinions or affiliations that the author(s) may have.*

Please keep an eye out for these and other WLA blog posts on our Facebook page and in the WLA newsletter. All blog posts are also archived and easily accessible on our website.

Habitat Leasing Opportunity through USDA’s Grassland Conservation Reserve Program Grows with Important Changes in Western States

By WLA |

New bill would scale up voluntary, locally-led big game conservation on working lands

By Louis Wertz |

Join WLA to stay up to date on the most important news and policy for land stewards.

Become a member for free today and we will send you the news and policy developments critical to the economic and ecological health of working lands.

WLA works on behalf of landowners and practitioners throughout the West. We will never share your contact information with anyone.